Creating Joyful Schools: A New Vision for Engaged Learning

Preamble: The blog post below was crafted through an innovative process using ChatGPT as a journalist. I provided it with key information about my educational philosophy, some of the readings I’ve been reflecting on (including the graphic shared below), and then asked it to generate interview questions. I engaged in the interview in audio mode, responding to these questions in real-time. The post you’re about to read is the result of that interview.

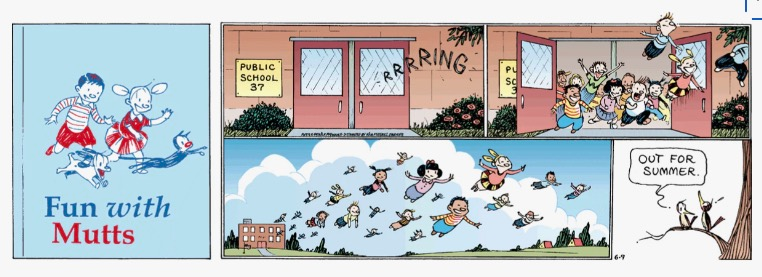

At the start of this summer, a cartoon caught my attention and made me reflect… The image humorously depicted students eagerly flying out of school, a visual representation of the traditional end-of-year excitement. But this image got me thinking: what if we reimagined schools as places students and teachers would joyfully float into, rather than out of? After 43 years in education, I’ve seen firsthand the power of such a transformation, and I believe that creating joyful, engaging learning environments is not just a dream but an achievable goal.

The Inspiration Behind the Journey

I didn’t set out to become an educator. In fact, it wasn’t until I found myself substitute teaching in a science classroom, 22 years old and fresh out of college, that I discovered a passion I never knew I had. Helping students grasp complex concepts ignited a passion within me, setting me on a path that has transformed my future in ways I continue to appreciate. Those first students gave me permission to see the power of making learning fun and accessible.

Starting as a math and science teacher, I quickly saw that students thrive most when they are actively involved in authentic work. Whether it was having them measure the density of a mystery material or design a projectile to hit a target, I saw that learning was most meaningful when students were doing, not just listening. This realization pushed me to rethink my approach to teaching and assessment, gradually moving me away from traditional methods to a more student-centered, constructivist model. These hands-on, minds-on pedagogies like “Introductory Physical Science” (Haber-Schaim) and the “Modeling Instruction Program” (ASU) gave me methodologies that pushed my thinking about learning by doing. Moreover, they showed how good professional learning should be structured.

The Limitations of Traditional Education

Graphic from: Mehta, J. (2023). Possible futures: A new grammar of schooling. Phi Delta Kappan.

One of the most pivotal moments in my career came in 2010, during the first year of the Mid-Pacific Exploratory Program. A ninth-grader, just a month into the program, told me, “I appreciate what you’re trying to do here, but if you let us learn the way we wanted to, with the topics we wanted, we would learn more, better, and faster.” This student’s candid feedback was a powerful reminder that while brief teacher-centered instruction can sometimes effectively launch a lesson, it is not the goal nor the most effective approach for deep understanding and knowledge transfer. I wasn’t able to completely throw everything out the window that day, but I started a process to get closer to that ideal. How could I create learning that felt student-driven and responded to the questions they had instead of just the content I knew?

The challenges facing traditional education are deeply rooted in what’s been coined as the “grammar of schooling.” This concept, explored in research by Tyack and Cuban in "Tinkering Toward Utopia," refers to the entrenched structures and routines—like bell schedules, age-based groupings, and standardized curricula—that resist change. These elements, though comfortable and familiar, often stifle the dynamic, personalized learning experiences that students crave and deserve.

Embracing Deeper Learning

My journey with Deeper Learning began long before it had that name. Early in my career (way back in 1982), I was introduced to a pedagogical approach called Introductory Physical Science, which focused on guiding students through lab experiments to discover the principles of matter. This hands-on, inquiry-based method resonated deeply with me, laying the foundation for my ongoing commitment to student-centered learning. In this approach to learning, students are scientists, historians, writers, mathematicians, not just reading and memorizing facts about specific content. For example, instead of having students memorize causes of an historical event, Deeper Learning makes the discovery of these details necessary to solving a compelling question or challenge.

Over the years, I’ve seen the profound impact of Deeper Learning in various settings, particularly in the Mid-Pacific Exploratory Program. Here, students are immersed in integrated projects that combine humanities and STEM, working in teams to solve real-world problems. Over the past decade, our students have supported local agriculture, investigated water quality in their community, produced solutions for cheap urban transportation, and advocated for social justice and environmental issues with partners such as the Honolulu Zoo and Blue Planet Foundation. The results have been remarkable: students not only master academic content but also develop a strong sense of identity, purpose, and agency. Many have told me that these experiences were pivotal in shaping their future aspirations. To see an example, take a look at a video of my colleague Gregg Kaneko’s class supporting Paepae o He'eia and their effort to restore an ancient Hawaiian fishpond here.

Lessons Learned and the Power of Joyful Learning

Reflecting on my career, one of the most important lessons I’ve learned is the value of creating learning experiences that are both challenging and joyful. As John Dewey famously said, “We do not learn from experience… we learn from reflecting on experience.” This quotation has guided my philosophy, reminding me that learning should be an active and reflective process. When we take the time to reflect on our learning, we create space for the appreciation and enjoyment of that process.

Joy is not just a nice-to-have; it is a crucial element of meaningful learning. When students are engaged in playful, joyful activities, their brains are more receptive to new ideas, and their learning is deeper and more lasting. This is why I believe schools should be places that students and teachers look forward to entering every day—spaces where learning is not just a requirement but a source of joy.

In Pasi Sahlberg’s book “Let the Children Play,” he makes a compelling case for the importance of play in children's development, arguing that play is not just a break from learning but a vital part of it, fostering creativity, problem-solving skills, and emotional resilience. I argue that this is just as true for adults. We often use other language—tinkering, passion projects, hobbying, crafting—but exploration, iteration, connection and joy are present all the same.

Rethinking School Structures and Meetings

To foster this kind of environment, we must rethink not only our classrooms but also the structures that support them. For example, faculty meetings are often seen as a necessary evil, a time-consuming task that pulls teachers away from more productive work. However, a recent article in EdWeek entitled “A Guide for Faculty Meetings That Couldn’t Have Been an Email” argues that these gatherings can be reimagined to be more engaging and productive. By focusing on collaboration, shared learning, and actionable outcomes, meetings can become opportunities for growth rather than just obligations. They should also be places for laughter, connection, and joy. Strong school cultures look the same at all levels, whether it is administration, faculty meetings or classrooms. We should see the same connection, joy and commitment with leaders, with teachers and in classrooms. In all areas, we should see active participation so that adults and young people get to "tinker," receive feedback and be actively engaged. This kind of culture and its benefits are supported by research (Linda Darling Hammond, Laura Desimone, Learning Forward).

Similarly, our schools must evolve to reflect the needs of today’s learners. We need to move away from rigid schedules and standardized testing as the sole measure of success. Instead, we should create flexible, multi-age learning environments that encourage exploration, creativity, and the development of each student’s unique gifts. The work of organizations like Fielding International, the wonderful book “The Third Teacher” and “Make Space” by the Stanford design team showcase models of design and innovative learning spaces, offering valuable insights into how we can make this vision a reality.

Looking Ahead: The Role of Technology and Leadership

As we look to the future, technology—particularly generative AI—offers exciting possibilities for education. While it is not a replacement for teachers or the right answer all the time, AI has the potential to provide personalized support for both students and teachers, acting as a tireless mentor and assistant. By leveraging AI thoughtfully, we can enhance learning experiences and free up educators to focus on what they do best: inspiring and guiding their students.

Leadership, too, plays a crucial role in this transformation. Educational leaders must model the practices they wish to see in classrooms, creating a culture of continuous learning and innovation. By supporting teachers with the time, resources, and professional development they need, leaders can help cultivate the joyful, student-centered environments that our schools need and deserve. These ideas of school-wide culture and symmetry are found in the Harvard University “Deeper Learning Districts” initiative, where school leaders work on equity, deeper learning and community for all the humans in their school organizations. In our efforts at Kupu Hou Academy at Mid-Pacific Institute, we have started working more systematically. It has pushed our thinking about creating more human-centered schools—for both students and adults.

A Vision for Joyful Learning

In the end, the goal is simple yet profound: to create schools where students and teachers alike are eager to engage in the work (and play) of learning. I can’t emphasize it enough—the way we all learn best is through passion, engagement and joy. If we love something, we commit to doing it well. If you want to see a great example of this, look through Ron Berger's Models of Excellence from the EL Education network. By embracing the principles of joyful, experiential learning, rethinking our structures and practices, and leveraging the power of technology, we can build educational environments where everyone floats in with enthusiasm, rather than flying out at the first opportunity. It’s a vision worth striving for—and one that I believe is within our reach.

Mark Hines has taught, learned, and played for 43 years as a math, science, and technology teacher, technology coordinator, program head, canoe paddling coach, deeper learning evangelist, facilitator of learning, and champion of teachers and learners of all ages. He believes that schools can collectively prepare learners for their future by providing them with authentic, engaging, and fun experiences.