Becoming a Teacher for Becoming Teachers

On March 11, 2020 — a day coined “The Day Everything Changed” by one National Public Radio reporter — I found myself, naively and perhaps a bit reluctantly (but not nearly reluctant enough), making my way to JFK airport.

While most people were hunkering down in the midst of a global meltdown, I was preparing to board three different flights. The first would take me to Nairobi, Kenya, followed by a flight to Kampala, Uganda, where two days later, I would board a flight to Arua - a city situated 475 kilometres (295 miles) northwest of Uganda’s capital, where I was set to kick off a three-year teacher training program with a group of 12 Sudanese teacher trainees.

Thinking back, I recall JFK Airport seemed eerily empty. I also embarrassingly remember myself ignorantly, though quietly, scoffing at a few people in the security line who were wearing masks. I then foolishly boarded the plane, and nearly 14 hours later, landed in Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi. After disembarking and making my way to my next gate, my phone rang. It was my husband. He sounded concerned and then proceeded to tell me that the NBA had announced the suspension of the 2019-20 season, indefinitely, Trump had suspended all flights from Europe, Fauci had reported, “It’s going to get worse”, and the World Health Organization declared that COVID-19 was in fact a pandemic.

There I was sitting in an airport in Kenya. I looked around at the bustling Nairobi airport. Everyone seemed casual and unperturbed. I whispered down the phone line, “What should I do?” I had just flown 11,841 kilometers (7357 miles), surely it would be crazy and extravagant to turn around and head back to New York City, right? My husband didn’t have the answer and my lifelong affliction with indecision meant there was no way I was going to make a decision before my next flight. So I boarded the plane to Kampala.

In the end, I had traveled to Uganda for a total of three days before catching a return flight to New York City - the epicenter of the pandemic in the US at the time. In retrospect, it turned out to be a sound decision. The Ugandan airport eventually shut down completely and did not open again until October 2020.

Back in Manhattan, while trying to breathe through the reality of what was happening just outside our apartment, I was also grappling with how to adapt my face-to-face training to a remote and online format. By some stroke of luck, the head of the organization had only weeks earlier delivered two laptops and provided each of the teacher trainees with a smartphone. Little did he realize what a lifeline these would become. While online teaching and learning posed many challenges, especially considering that our teacher trainees had limited technological experience, we managed to progress steadily. This challenging transition highlighted the essential role of flexibility and creativity in education, highlighting the need to continually evolve our teaching practices to meet students' needs.

In November 2020, after months of managing the challenges of online learning, and one month after Uganda reopened its airport, I was on my way back. This time masked, shielded, and ready to spend “face to face” time with the teachers-to-be.

Three Years Later: Becoming Teachers

The most important realization I made along the way was that to help these individuals become teachers - individuals who had and continue to live such different lives than me, in such different circumstances, with far less opportunity and privilege than myself - they had to be given the opportunity to think about their beliefs about education, teaching, and learning, and to be willing to consider an alternative. It was more about a mindset shift than anything else. You see, for the majority of their educational journeys, these students had sat in teacher-directed classrooms, being talked at and made to copy notes off a board. This was their story of learning.

I remember a group of the teacher trainees sharing the story of their “permissive” history teacher. They described the following: The teacher would enter the classroom, open up the textbook and start reading verbatim. Students would come and go, yet she barely lifted her head from the textbook. Those who stayed and were interested, furiously scribbled down important dates and names, trying to gather the information necessary to pass the next test.

This story helped me better understand the power of external experiences that can impact decisions and choices. There are times when "we" do what has been done to us. Other times we stand up and break free from tradition or expectations - the way it’s always been done - to be and live differently.

Our Stories of Learning

In the teacher training program, one learning task required the participants to delve into and document their personal learning stories. What is a "story of learning"? I described it as an individual's personal narrative, shaped by their experiences and perceptions throughout their educational journey. It includes details about the teaching methods, the interaction (or lack thereof) between students and teachers, and the overall atmosphere of the learning environment. Their stories revealed how these experiences had a lasting impact, either positive or negative, on their interest in learning and their attitudes toward specific subjects.

As future teachers, these students were embarking on a journey to redefine their narrative of teaching and learning. To accomplish this, there were two important steps they had to take. One, it was crucial for them to experience for themselves what learning could look like, feel like, and sound like. But they also needed to reflect upon their own existing perceptions and stories about learning - what it had looked like, felt like, and sounded like when they were in school. Without this critical self-reflection and comparison, there was a risk that they would simply replicate the educational experiences they had had, possibly perpetuating the same stories they had been told.

“After all, we began our on-the-job training as teachers when we were 5 years old. Our beliefs about school, classroom management, and discipline have been shaped by years of experience, starting in our first year of school” and often earlier - at home. (Smith et al., 2015)

Our stories of teaching and of learning are created, shaped and influenced by our own experiences of teaching and learning. Questioning and reconsidering all of our existing “stories” - our beliefs, attitudes, behaviors - is key to making positive change. As Steve Covey said, “Unless a person can say: "I am what I am today because of the choices I made yesterday," that person cannot say, "I choose otherwise.” The sharing of learning stories was essential to the training.

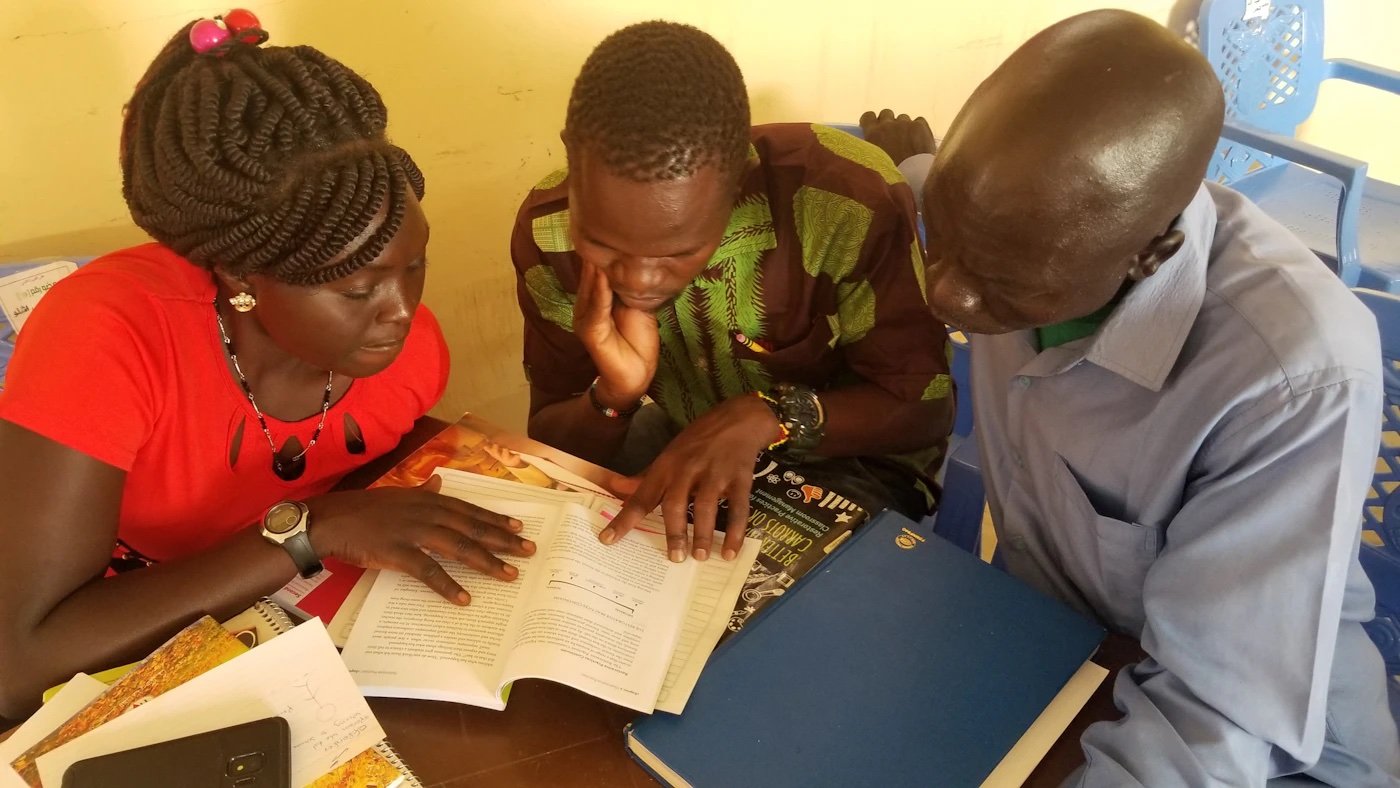

Image: A debrief session after observing our teacher trainees leading a morning meeting

Here is an example of one teacher candidate's learning story:

Chamu, Sudanese Teacher Trainee

"I remember that the teachers did not call us by our names and we didn’t have time to interact with one another (teachers or peers) and that meant we didn’t develop positive relationships with each other. Teachers would punish us if we didn’t pass a test, so because of that we only read to pass the test and please our teachers but not to understand what we were reading or learning. We were not given a chance to speak our thoughts or share our ideas or even ask questions.

I remember that teachers would come to class with the textbooks and only give us ideas from the book, never from the learner's ideas or thoughts which did not help us to learn from each other. We only did what the teacher told us to do. So what I learned was that a teacher is someone who we learn from or a teacher is someone who knows everything. My learning time was not good because the way teachers were teaching us was not engaging." - Chamu, Sudanese Teacher Trainee

Chamu's story highlights a crucial component of teacher development: the understanding that personal educational experiences, especially the challenging ones, can deeply inform and improve one's own approach to teaching when we take time to reflect upon them and see that there is a possibility for something different - the possibility of what schools and learning can be.

Her realization that education should go beyond rote learning and that it should involve engaging with, respecting, and understanding each student's unique perspective and ideas is fundamental. In Chamu's future classroom, one can imagine a space where each child is known by their name, encouraged to express their thoughts, and inspired to learn not just for tests, but for the joy of learning itself.

Perhaps challenge yourself to reflect on the following question: How do your experiences shape your approach to teaching and learning, and beyond? Change is a courageous act. It relies on the admission of the need for change - a process that often involves confronting uncomfortable truths about ourselves or our circumstances. It demands not only the acknowledgment of past limitations or mistakes but also the bravery to envision and pursue a different, often uncertain future.

“Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better. ”

Image above: Teacher Rashid leads the group in a game of "Follow the Leader".

What does it mean to be a teacher?

This is an important question that anyone involved in teacher education has to consider. So one day I posed this very question to the group. Here are their unedited responses:

A teacher is a person who gives ideas or knowledge to other people about what they don't know or they know about it but he or she builds on the knowledge for betterment.

A teacher is a person who gives knowledge to the students.

A teacher is someone who passes knowledge from one student to another without discriminating against the students.

A teacher is a person who takes up the responsibility of giving information from one person to another both formally and informally.

A teacher is a person who helps learners to get knowledge.

A teacher is someone who gives knowledge to anyone or a person who teaches.

A teacher is a person who teaches people new knowledge of what they don't know.

Is a person who helps and guides them on new discoveries.

A teacher is a person whose occupation is to teach.

Teacher is a person who transfers knowledge to people who do not by guiding them between the wrong and right diplomat.

Without exception, the definitions all put students in the passive role - the recipients of knowledge - and the teacher as the all-knowing sage on the stage, the person delivering or transferring knowledge.

We then started to reflect upon all that we had learned up to that point and began to expand the definition. Teacher trainees worked in groups, talking about all the responsibilities and roles of teachers and learners. Using this information, the teachers were asked to create a working definition of a teacher. Each of the groups presented their definitions and then we workshopped them as a group, aiming to create one final TMM definition of what they wanted teachers to be in Nuba.

After days of discussions and watching videos of student-centered classrooms, the teachers eventually created the following definition of a teacher:

“A teacher is a person who teaches, guides, assesses and inspires his or her learners, and creates an engaging environment where students feel safe and belong. He or she helps learners to acquire knowledge, discover things, formulate ideas, and develop skills, to allow them to learn long after they leave the classroom."

Articulating their Learning

During the second year of the three-year teacher training program, we had an unplanned opportunity to gain insight into the teacher trainees' evolving thoughts on teaching and education. Mike, a volunteer videographer, came by to capture some footage and interview me and some of the teacher candidates. These interviews were completely spontaneous — the candidates volunteered on the morning Mike arrived, and they weren't given any questions beforehand. I was in the classroom teaching and didn’t think too much of it. A month later, Mike shared the following video. I believe it speaks for itself.

The truth is that no matter where someone is in their journey of teaching, whether they are applying for teacher’s college or a 30-year veteran winding down his or her career, the truth is that we are always becoming teachers.

References:

1. Smith, Dominique, Douglas Fisher, and Nancy Frey. Better Than Carrots or Sticks: Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management. Alexandria: ASCD, 2015.

2. Covey, Stephen R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1989.

Laura Manni is an educator and communications professional with international experience in North America, Africa, Europe and Asia. She has facilitated learning in diverse settings, from early years classrooms to non-profit offices in NYC to rural communities in Africa. She is currently the Director of Teacher Development wth To Move Mountains, an organization whose education programs aim to support long-term solutions to chronic effects of war. She completed her honours Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Education at York University in Toronto, Canada and her Masters of Education at Cambridge University, in the UK. She also holds a certificate from Project Zero’s Creating a Culture of Thinking from Harvard University, which has played an impactful role in her teaching.